Books I Read, January 4th 2026

Happy New Year. Spent the better part of the last several weeks baking, cooking, eating, drinking, laughing with friends and family, and reading Proust. I hope that 2026 brings anyone exactly what you deserve, and maybe even a little more besides.

The Prisoner by Marcel Proust – The fifth book of Proust’s masterpiece details his obsessive, jealous love for Albertine, and his efforts to keep her contained for a long period in a wing of his house. Albertine is, for me, the great weakness of the book—or perhaps one of two, the latter of which I’ll detail further down. She never comes across as a fully realized character. To some degree this might be a deliberate choice, as Proust is much more concerned about the effect of love on our inner landscape than of love per se. His obsession with Albertine, rather than Albertine itself, constitutes the bulk of the narrative. But still, without some stronger anchor his jealousy seems arbitrary and inaccessible—something which is not improved by the sapphic lens of his obsession, itself a difficult peculiarity to share. Probably more importantly, the jealousy itself, although presented as a universal quality of romance – it being prefaced with Odette and Swan’s union, not to mention St. Loup and Rachel – isn’t that at all, but (seemingly) a particular obsession of Proust. So much of what Proust writes finds echoes in our own minds, even on the most complex and subtle topics, that this long, dissonant note can’t help but ring out.

The Fugitive by Marcel Proust – The sixth book of Proust’s masterpiece details Marcel’s forgetting Albertine and going to Venice. Further Proust points will be explored below.

Time Regained by Marcel Proust – The final book in Proust’s masterpiece acts as an extended epilogue, skipping ahead to the miseries of WWI, and further on still to a period where our protagonist, after an extended stay in a sanitarium, briefly returns to Parisian society, finally striking upon the grand understanding of time which will allow for the creation of his epic work. Speaking of the work as a whole, it is at once supremely brilliant and somehow less than the sum of its parts. Proust has a profound grasp of the human mind, as well as the subtleties of social interaction and the role which our subjective perceptions and endlessly shifting memory play in our experience of existence. Indeed, there are insights galore in these pages, complex but valuable. And yet, the peculiarities of Proust’s own character – his obsessive jealousy, his inability to feel genuine friendship, indeed his essential incapacity to love in a true sense – render much of his thinking alien, at least to me, and, I would suspect, to most readers. This would be fine—there is enormous value in elucidating even an aberrant mind state – except that Proust isn’t interested in the subjective, but only in (as he says many times throughout the book) the general laws which can be drawn from it. And Proust definitely seems to believe that the truths he articulates are universal, that all love is simply refined jealousy, that we exist almost exclusively within our own conscious, that social interaction is essentially a barren distraction from one’s own psyche, and that happiness is impossible as our desires, once granted, immediately cease to offer any satisfaction. But I don’t think these things are true, or at least are true only in part, and so much of Proust’s grand summations are somewhat lost on me. That said, this remains one of the seminal works of human letters, a profound and magisterial depiction of the movement of time, nostalgia, love, sex, so on and so forth. In short, it was well worth my December.

The Thin Man by Dashiell Hammett – A pair of high-functioning alcoholics investigate a murder. Needing a break from Proust, I read half a dozen classic noirs as a palette cleanser. This is probably my least favorite of Hammett's slim ouvre, I don't really care for Nick and Nora does nothing but say 'you're amazing!' to him for about two hundred pages. Also, I'm far from a teetotaler but if anyone you knew drank like this it would be of serious and immediate concern. That said, there are some really stellar moments where you're reminded that Hammett, alone among the grand masters of the genre, had actual experience as a detective, glimmers of reality that his competitors can't really match.

After Dark, My Sweet by Jim Thompson – A mentally ill ex-boxer gets drawn into a kidnapping plot. One of Thompson's best, as swift and brutal as a punch to the head. The sense of dread builds from the first line. No one wrote better 'damaged people make foolish decisions'-style noir than Thompson.

The Ferguson Affair by Ross Macdonald – An upright lawyer gets drawn into a web of murder. MacDonald is a better plotter than Hammett or Chandler, and he's a few drops wetter as well. Some of the 60's sensibility seeped into his work, giving him a sense of sympathy which stands out.

The Lady in the Lake by Raymond Chandler – Marlowe investigates a pair of missing woman. What Chandler loses in narrative logic he makes up for by being one of America's foremost mid-century prose stylists. Excellent.

The Outfit by Richard Stark – An amoral gunhand goes to work on an extremely loose depiction of the mafia. I admire Stark's willingness to make his anti-hero an absolute prick, and this certainly moves quickly, but there's an element of fanboyishness to all of it that kind of sticks in my craw.

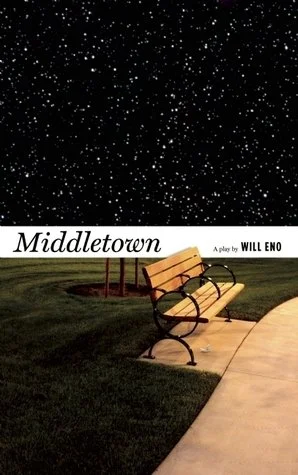

Middletown by Will Eno – A kindly, brief play about the absurdity and beauty of human existence. A nice little shot of optimism to start the new year.